What I've come to realize is that usually the movies that are spectacular don't have good stories, and I think it's because all the surface glitz, all the fast motion and staccato cuts and excessive spectacle is visual candy, meant to be addictive and leave you wanting more - and once you get sugar you don't want green beans and steak anymore. When you get the sugar rush going that's all you want anymore, until you get sick and puke it all up, and you're left feeling empty (a very apt description of my experience seeing quite a few modern blockbusters!) So it seems on a basic level the excessive spectacle and the meat and potatoes of storytelling are incompatible.

Though there was a time in the late 70's and early 80's when some of the New Hollywood filmmakers like Spielberg, Lucas and Ridley Scott were still doing good solid storytelling and just starting to develop the modern excesses of spectacle that are pretty much all today's blockbusters consist of - but they were using it sparingly, only to spice up the story - the effects were still in support of the story rather than the other way around. The last director I'm aware of who worked like this in the sci-fi effects genre was James Cameron - not the Cameron of today, but when he did his early films - up through around T2, when he was starting to give in to the call of spectacle and CGI. I still feel like T2 is effects in support of story, though the dynamics were starting to shift already.

From what I understand, Spielberg wanted to do Jaws very differently - he wanted to be able to see the shark all the time, for the camera to be able to follow it underwater while it did loops and crazy stunts, but the mechanical shark didn't look good enough to allow that, so it was only by a twist of fate that we ended up with an actually great movie rather than the spectacular effects extravaganza he wanted to make. Instead he had to fall back on traditional tricks like not showing the monster too much, letting the viewers use their imaginations to fill in the blanks. Apparently he thought that was sub-par, when in actuality it made it a much better and more sophisticated film. I was really shocked and let down to discover that the greatness of that film was something that happened by accident… I had more faith than that in Stevie boy! Sad to see it was completely misplaced.

I've been on a huge Cronenberg kick lately (of all things!) - I just read 2 books, one about his films and one composed of his own words from interviews etc, and decided to watch all of his movies, all as part of my studies of directors and how they work. I was pretty surprised to hear him say that he admires Bergman and Kurosawa and Godard and the other international directors of the postwar period and that he deliberately makes his movies like they did. Say WHAAAAT??!! At first I couldn't even comprehend what I just read - oh sure, Scanners, Videodrome and The Fly are just like The Virgin Spring or Seven Samurai!! Sure they are!

But after reading some more and watching his films starting from his first ones, I realized they actually are alike in many ways - there's no empty spectacle just to make it fast-paced for a modern popcorn crowd, but at the same time he doesn't (usually) do boring Drama movies about relationships or people trying to improve their social standing. I mean, he works in color, but so did Bergman and Kurosawa et al once that became cheap enough. And he does the crazy morphing body horror stuff - but that's the extent of anything spectacular in his work, and it's actually never just for shock effect or cheap horror scares the way Carpenter would use it - it's always to say something that the whole film is about - something philosophical about human nature. It's shocking, sure, but once you get past that (most people never do) and pay attention to what he's really doing, his films are actually built on very interesting philosophical ideas, not just on scares or gross-outs. All of Cronenberg's films turn out to be doing the same thing in different ways - physically externalizing an internal state --- manifesting psychological conditions literally in the flesh - done through body horror special effects in most of his early films, and through performance technique in everything from Dead Ringers on (everything after The Fly if I remember right, which isn't my strong point).

He did a film called Crash, which involved nothing but sex and car crashes, and still he didn't give in to the temptation to go all Hollywood Blockbuster style - the crashes are simple and quick, no explosions, no slow motion shot from 12 different angles, no elaborate setups or ticking countdowns or anything. No tough-guy muscle-head drivers spouting off cheesy one-liners. None of it is for exploitation, it's all to explore the ideas his movies are based on. His actors can really ACT - they're not models who decided to try their hand at being in Sy-Fy Channel style crapfests.

Actually the same is true of David Lynch and Kubrick too -both of whom Hollywood doesn't know what to do with because their work is about ideas and even though it flirts with the same material Hollywood uses only for cheap thrills it's used thoughtfully and intelligently - something severely lacking in Hollywood since sometime in the mid 80's at least.

And something I realized about all of them - even though they do use great cinematography and are known for it, it's never ostentatious and it always always serves the story rather than the other way around. In fact most of their cinematography is quite simple and straightforward - the reason it tends to look so nice is because they're shooting things that are inherently interesting and they carefully arrange visual elements for greatest storytelling clarity (not visual eye candy effect) and they or their cameramen (both in most cases) have a great eye for composition.

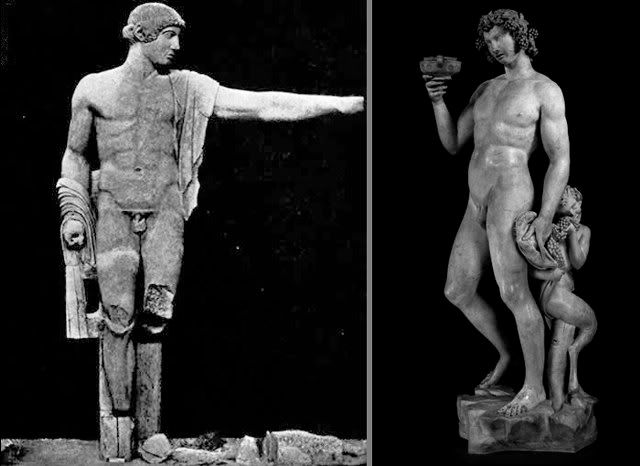

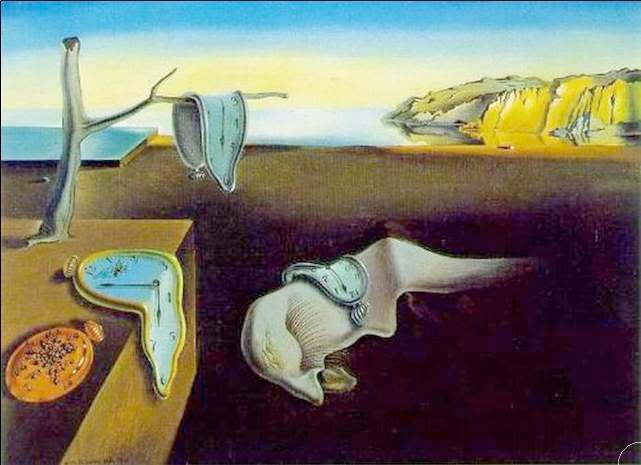

It might seem odd that I mentioned David Lynch in this article. He's different from the rest because his stories are usually pretty surreal and don't follow standard narrative convention. And like Cronenberg, his work shocks people raised on the standard Hollywood formulas and happy endings. But in spite of the sometimes frightening or nightmarish nature of some parts of his films, he's known as the Jimmy Stewart of surrealism. He looks a lot like Mr. Stewart, and in fact he describes his childhood as very Norman Rockwell. It was idyllic and serene, but he was always fascinated by the little red ants that swarmed unseen on the beautiful trees, and the weird patches of dripping slime. So most of his films focus on that dichotomy - a pastoral idyllic world that when examined closer reveals a nightmarish underworld hidden just beneath the surface, which erupts through from time to time. He also likes to examine themes of duality, many of his female characters split into 2 people (I think only one of his male characters does the same, in Lost Highway). This duality of human nature is actually one of the great themes running through the annals of human thought from the heady days of the Greek philosophers onward, with significant stops at Freud and Jung and throughout the great world literature. All of these directors concern themselves with thematic material that is pretty well known to readers of great literature or philosophy or psychology - it's just considered too difficult or challenging for Joe Six Pack and Suzie Homemaker, who would rather be watching American Idol or Real Housewives.

** EDIT:

I just made the connection between Lynch's idyllic pastoral neighborhoods erupting with insect plagues and slime with what happens to his human characters. It's pretty obvious once you've made the connection, but it's the same thing applied to landscape rather than person. In Lost Highway for instance the man and his wife both start off as happy, successful well-adjusted yuppie types until suddenly a mysterious video tape shows up one night that begins a series of transformations essentially ripping away that outer illusion to reveal the seething murderous shadow personae of them both lurking inside unsuspected. The same happens to Betty Elms/Diane Selwyn in Mulholland Drive - through most of the movie we see her shiny happy Hollywood Hopeful dream self, smiling brightly and all innocent, finding instant success and friendship on arriving, but little by little her Shadow self bursts through, which had always been there but unseen, unsuspected. It's the parts of ourselves we hide away because we don't want to own them, and when they do show their ugly faces we don't recognize them as ourselves. That's why he actually changes their names and has them played by different actors sometimes.

Ironic now that I posted the 2 names of the Naomi Watts character - her shiny happy character is even named for trees!

It's also the kind of thematic material I've discussed a few other times on this blog - most prominently in my articles about Gene Wolfe, a writer often relegated to the science fiction and fantasy shelves, but who says the type of work he does actually concerns itself with the biggest human issues - things that can't be touched by the very limited scope of the social realist novel, a genre that only arrived on the scene relatively recently and that according to him won't last very long. The great work of the world's most ambitious thinkers - Homer, Shakespeare, Goethe etc, does not limit itself to the workaday lives and ambitions of ordinary folk. It's true that in their most limiting genre forms science fiction and fantasy are extremely weak, but if a writer or filmmaker really wants to broaden his scope to include the full range of human experience and thought, then he needs to reach out to the outer limits, beyond the pale of everyday experience - and then you find yourself in uncategorizable territory, dealing with stuff that gets you classified as science fiction and/or fantasy, though really it may be closer in nature to myth. And that's one thing all the filmmakers I listed above definitely have in common. Well, many of them at least used-to concern themselves with this level of experience, but have since switched over to glitzy shiny empty spectacle, which brings in much better opening weekend box office. What is it this is called? Oh yeah, that's right - selling out!